Savitri Randhawa

Savitri Devi Randhawa (September 2, 1929- May 14, 2019) was an exceptional woman who lived a remarkable life. In her youth, she survived the horrifying trauma of the 1947 partition of India. Over a decade later, in 1961, she was one of the first Punjabi women to immigrate to the United States as a single woman to pursue higher education. She lived in Davis in the early 1960s while her husband, Narinder Singh Randhawa (March 13, 1927 – November 26, 1996), completed his doctoral studies in agriculture at UC Davis. Savitri finished a Master’s degree in psychology at Sacramento State University. Then she returned to India in the 1960s for several decades where she served as a Professor in Punjab. In her later years, she returned to Davis to stay with her family.

Randhawa family. Standing (left to right): Sarinder, Savitri, and Narinder. Seated (left to right): Anita, Gurinder, and Rupinder, Ludhiana, Punjab, India, c 1975.

Everyday I had to cry and shout, saying that I wanted to study further. It

was my mother who supported me. After a week, my mother told my father,

‘If my daughter is so keen to study further, I am going to take her to college

in Lahore.’

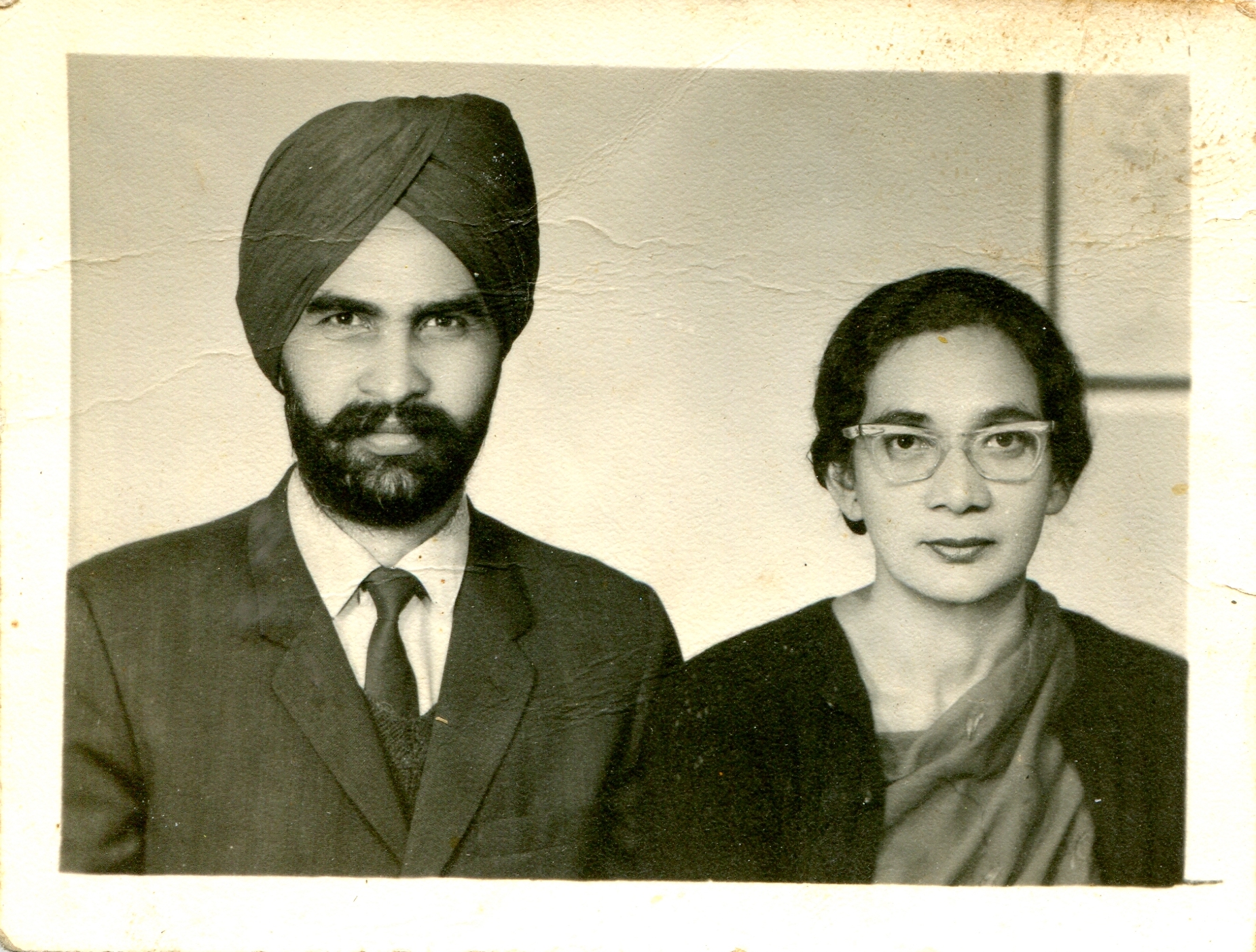

Narinder and Savitri Randhawa, Ludhiana, Punjab, India, c 1964.

Growing up in a progressive Sikh family in a small village in western Punjab (later Pakistan), Savitri believed that the girls and boys in her family were treated the same by their parents: “We were given equal choice and freedom as the boys.” Her mother, Gurbachan Kaur, came from a highly educated family. Savitri’s maternal grandfather was a physician. Her mother was educated, could read and write in Urdu and Gurmukhi, and stayed well-informed about current events by reading the newspaper daily. She was also quite devout and kept a Guru Granth Sahib (Sikh scripture) in her home. Savitri’s father was born into a modest family, but he was ambitious to pursue higher education and a professional career. He became a prominent attorney, primarily specializing in criminal law.

Savitri was fiercely determined to pursue higher education and a professional career. At first her father only supported her education up through high school. After completing high school, Savitri recalls how she “had to struggle hard” to convince her father to allow her to attend college:

With her mother’s steadfast support, her father relented. At her all girls’ college in Lahore, Savitri enjoyed developing friendships with girls from many different communities. With her new friends and teachers as role models, Savitri explained: “I got inspired that I could do something in life instead of just being a housewife.” After college, she pursued Master’s degrees in economics and education in India.

Savitri was just 18 years old when she experienced the devastation of the 1947 partition. Living in a region with a predominantly Muslim population in a small village in the Sarghodha district, Savitri’s family never imagined they would become refugees or that their lives would be in danger after India’s independence from British rule. The family had enjoyed intimate bonds of trust and friendship with Muslims over the course of their lives.

We were protected by Muslims before we shifted to India. There were two to three Muslims who would sleep in our house to protect us…

No one could dare to touch us… We did not know it was going to be that horrifying of an experience as it happened to be in later life.

Without any notice, Savitri’s family were forced to leave their home across the new international border for India for their safety.

The family hurriedly boarded a train bound for India, Savitri recalls: “When we took the train, it was so crowded that there was hardly a place to sit. After just fifteen minutes, the train stopped and there was firing outside… Muslims attacked the train.” Fortunately, no one was murdered during this incident. Finally, the family was brought to a refugee camp. She remembers living in an individual house in the camp, but the family remained hungry during that time. Finally, they occupied a home that had just been vacated by a Muslim family that had fled in the opposite direction to Pakistan. It took many years before her family could recover and start their lives over again in India. As she recalls, the difficult situation they found themselves in “was unimaginable for us” because previously they had enjoyed such comfortable lives. Members of her extended family were also murdered during the communal violence that took the lives of over one million people in all religious communities.

What is remarkable about Savitri’s narration of the trauma of partition is her lack of bitterness and reproach. Instead, she drew profound lessons from this terrifying experience. After growing up in comfort, she could only bring two dresses with her as she fled during partition. The experience utterly changed her outlook on life.

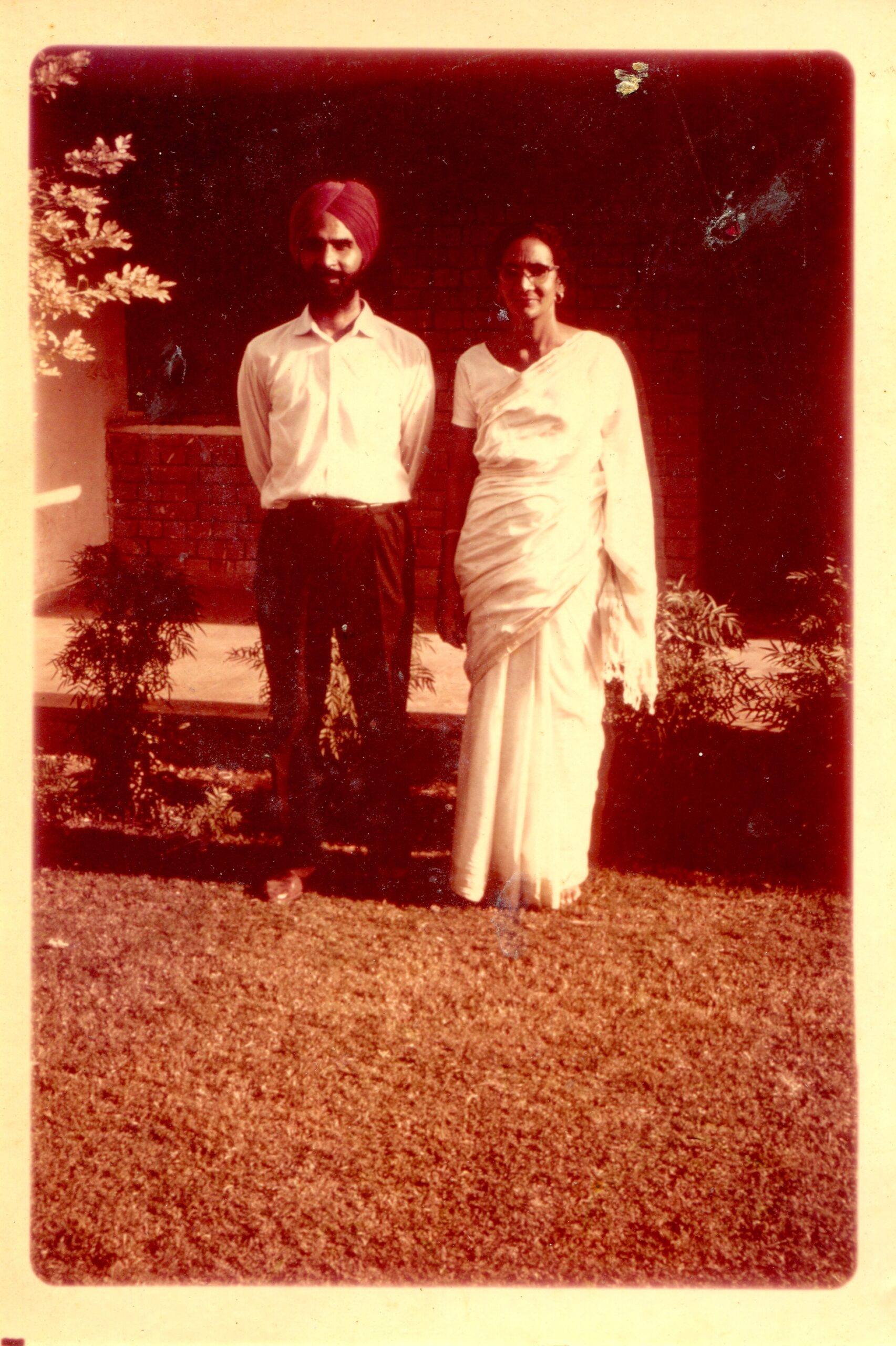

Narinder and Savitri, India, 1960s.

Today you have plenty, tomorrow you may not have anything. I saw that….

One should not be proud of riches and material wealth because it’s short-lived.

You never know when it could be snatched.

She also does not blame any religious community for the violence. She laments the cruelty of all of the communities during partition. “I have no ill feelings,” she emphasized: “I have only good feelings for Muslims.”

In 1959, after completing her Master’s degree in education and working in Delhi, Savitri and her future husband, Narinder Singh Randhawa, met for the first time at her father’s friend’s home. Their families had arranged the meeting for the goal of arranging their marriage. Both Savitri and her future husband intended to pursue higher education in America. At a time when most couples in Punjab never saw each other prior to marriage, her parents were quite liberal in their thinking. They wanted Savitri to be able to see and talk to her prospective husband before the wedding was arranged. Savitri approved of marrying Narinder: “He had a good education and good prospects. I was interested in a job, not sitting home and being a housewife. I liked that he was going for a Ph.D. I could see his future prospects.”

On September 30, 1961, Savitri traveled to the United States as a single woman intending to pursue graduate studies. Her brother, who was also completing graduate school in the US, had told their father to send Savitri to America for higher education. The families had agreed that Savitri and Narinder would marry shortly after her arrival in the US. Within a short time, Savitri joined her husband in Davis, CA where he was completing his Ph.D. in agriculture. As soon as Savitri arrived in California, she was married to Narinder at the Gurdwara in Stockton, CA on October 12, 1961. It was a very simple ceremony without any family members present. Their small group of friends in Davis cooked dinner for the newly married couple in celebration.

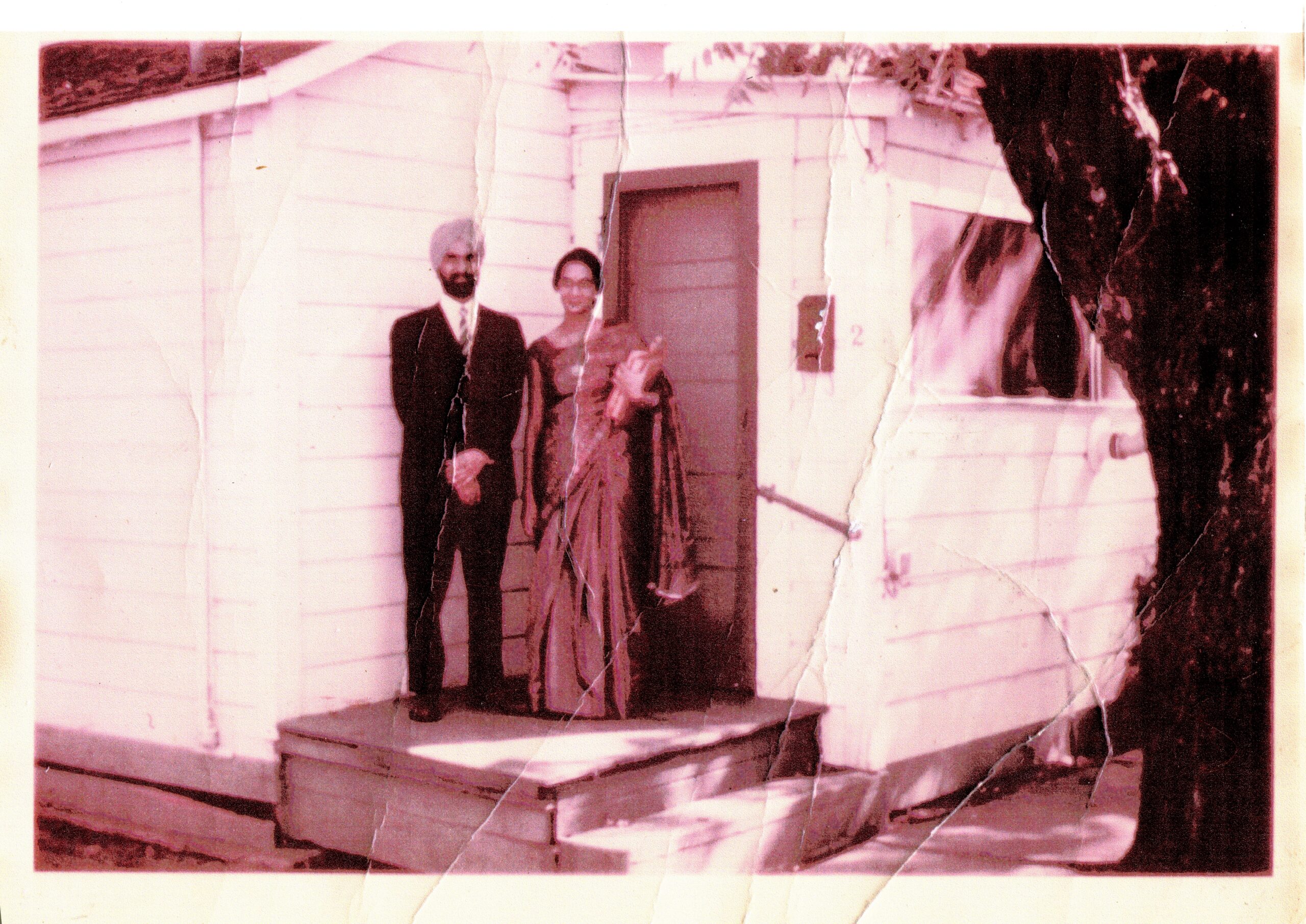

Narinder and Savitri Randhawa at their home near Third and D street corner downtown Davis, 1961. The day after their wedding.

After marriage, Savitri combined her graduate education with raising a family. She and Narinder raised four children, two from his previous marriage and the two daughters they bore together. Although Savitri had gained admission to a doctoral program in education at UC Berkeley, she and her husband jointly decided that it was not feasible for her to commute to the Bay Area from Davis. Therefore, she completed her Master’s degree in Psychology from Sacramento State University.

Shortly after obtaining his doctoral degree in 1964, Dr. Narinder Singh Randhawa landed a prestigious professorship at Punjab Agricultural University. From 1967-77, he led a nationwide project on micronutrients in soil for India. Eventually, her husband served as the Director General of the Indian Council on Agricultural Research (ICAR). He earned an international reputation as an agricultural scientist who helped discover the principle of micronutrients in soil. Dr. Randhawa found that the micronutrients were deficient in Punjab soils. This finding led to the amelioration of soils in his native state by adding micronutrients that improved the soil fertility and ultimately enabled higher yield crops. He also received the Padma Bhushan in 1989 for his contributions to agricultural research in India.

Savitri also achieved a distinguished career as a professor in Punjab. She served as an Associate Professor and Principal of the College of Education at the Malwa Central College of Education in the city of Ludhiana, Punjab. Of all of her professional achievements, she said she felt most proud to serve as a professor in Ludhiana.

Decades later, after her husband had passed away, she returned to Davis, CA where her daughter lives. She asserts that if Davis was as multicultural as it is today, then she would not have returned to India in the 1960s, adding: “If Davis in the sixties was what it is today, I would not think of going back to India. I feel very comfortable here now.”

Photos courtesy of Savitri Devi Randhawa.

Sources: Interview with Savitri Randhawa by Nicole Ranganath, Davis, CA, December 19, 2017, with extensive additional input by Savitri Randhawa and her daughter, Anita Dhesi. Professor Gurdev Khush also provided information on the significance of Dr. Narinder Singh Randhawa’s agricultural research.